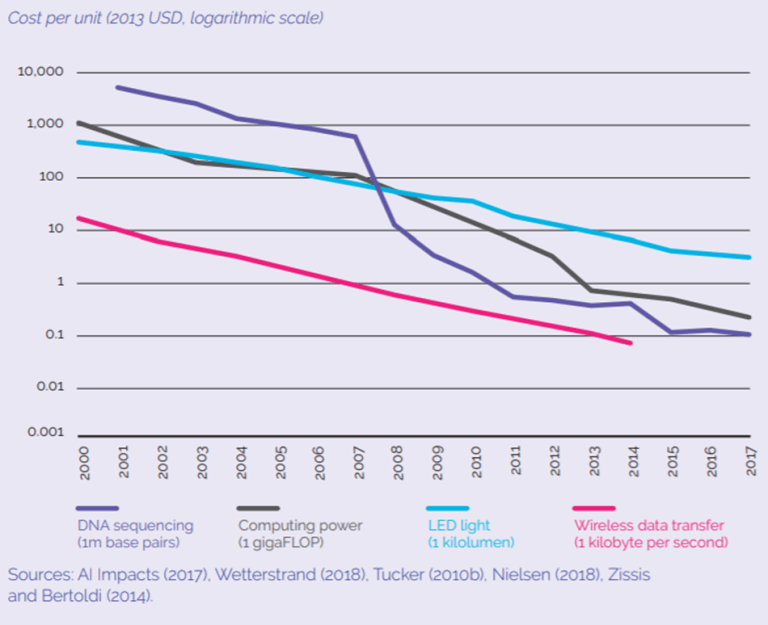

ver the past 20 years, the increase in computing power by about eight to 10 orders of magnitude has brought the costs of using digital technologies down to a tiny fraction of their year 2000 levels (Figure 1).

Contents

Figure 1. The costs of using many technologies are dropping rapidly

From Charting Pathways for Inclusive Growth: From Paralysis to Preparation, Pathways to Prosperity Commission, 2018.

Eight orders of magnitude is quite substantial: Lant Pritchett notes that it is the ratio of the United States’ GDP to his personal annual income. The decline in costs is unlike that for any other technological innovation. It would be the equivalent of automobiles costing between $2 and $21 today (the Ford Model-T cost $850 in 1908 or $21,340 in 2012 dollars), or refrigerators costing between $1.50 and $15 today (they cost around $14,000 when they first came out).

During this period, levels of overall government effectiveness have hardly changed (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Government effectiveness scores

Source: Worldwide Governance Indicators, 2017

To be sure, there have been some successes in digital technology improving certain government programs and processes. Biometric registration, verification, and payment systems in India’s National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme reduced leakages of funds by 35 percent. Electronic tendering of contracts increased procurement competitiveness and the quality of roads in India and Indonesia. One-stop, computerized service centers in Karnataka, India enabled citizens to receive birth and death certificates with, on average, 3.4 fewer visits, 58 fewer minutes per visit, and 50 percent less chance of being asked for a bribe compared to a typical government office. And mobile phone based monitoring of service providers reduced their absence rates by as much as 25 percentage points in India, Pakistan, and Uganda.

Despite these individual successes and considerable evidence that technology has improved productivity in the private sector, overall public-sector effectiveness does not seem to have been affected. Why not?

Three possibilities:

1. As the World Development Report 2016 suggested, technology requires complementary analog inputs to register an increase in effectiveness. Even if routine tasks can be automated, the final output requires human intuition, judgment, and discretion to be productive. While this argument is compelling in the abstract, it is hard to imagine that an eight-orders-of-magnitude decline in the price of the digital input hasn’t had some effect on this joint product. The elasticity of substitution between the digital and analog inputs must be precisely zero for this to be the reason that overall government effectiveness has not improve

2. Public bureaucracies either do not want to—or cannot—adapt to digital technologies. They may not want to because, in a government setting, efficiency improvements may lead to a reduction in the agency’s budget. Also, better record keeping and greater transparency make it harder for bureaucrats to capture the rents from government procedures.

Bureaucracies may not be able to adapt to new technologies because they simply lack the infrastructure. In Ethiopia and Nigeria, local government officials have access to the internet 22 percent and 3 percent of days, respectively. Furthermore, public officials continue to use tacit knowledge to inform decisions. In Ethiopia, 90 percent of public officials get information from field visits and personal interactions, rather than management information systems.

But lack of investment in technology cannot be the whole story, since several countries such as India and Rwanda have a digital adoption index that is higher than their per capita GDP would predict. Yet neither country has seen an improvement in its government effectiveness index.

3. Digital technology creates monopolies, whereas the function of government is either to break up monopolies or to prevent becoming a monopoly of its own. Technology creates monopolies because the marginal cost of production goes down, and the marginal benefit to the user goes up, with the number of users in the system, as Uber or Facebook have shown. The private sector has embraced technology and seen increases in productivity precisely because it has enabled them to exercise monopoly power. The essential reason is that, with computers, the identity of the machine can be known easily (the IP address), but the identity of the user can only be known if the user provides it. This creates a huge incentive to centralize information about users, which gives the owner of that information monopoly power.

This centralization of information cuts both ways for government effectiveness. On the one hand, for those activities where discretion at the local level is not needed, centralized information can exploit economies of scale and improve efficiency. Among the success stories mentioned above, payment systems, procurement, and issuing birth certificates are all examples of activities that require very little discretion at the local level. On the other hand, for a large number of public-sector activities, including teaching, there has to be a balance between centralized and decentralized authority. While the central authority can monitor whether the teacher is absent or not, it is only information at the classroom level that enables the teacher to teach effectively. In fact, even the benefits of reduced teacher absenteeism seem to have dissipated after a few years.

In short, to improve government effectiveness across the board, the technology needs to be adapted to situations where some information is held at the local level while other information is at the central level. Interestingly, Tim Berners-Lee, the founder of the World Wide Web, is developing a similar system whereby all of a person’s information is stored in a Personal Online Data (POD) store that only the individual can access, while the internet remains free. Such a system may give governments the appropriate flexibility to tailor their systems and enhance overall effectiveness.

[“source=brookings”]