On September 28, 2016, a 3-year-old girl named Elodie Fowler slid into an MRI machine at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital in Palo Alto, California. Doctors wanted to better understand a rare genetic condition that was causing swelling along the right side of her body and problems processing regular food.

The scan took about 30 minutes. The hospital’s doctors used the results to start Elodie on an experimental new drug regimen.

Fowler’s parents knew the scan might cost them a few thousand dollars, based on their research into typical pediatric MRI scans. Even though they had one of the most generous Obamacare exchange plans available in California, they decided to go out of network to a clinic that specialized in their daughter’s rare genetic condition. That meant their plan would cover half of a “fair price” MRI.

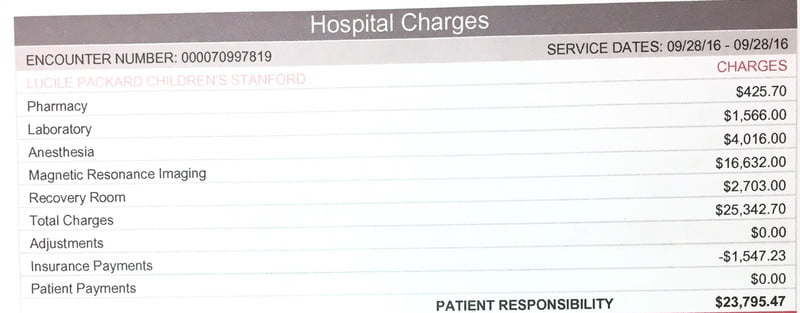

They were shocked a few months later when a bill arrived with a startling price tag: $25,000. The bill included $4,016 for the anesthesia, $2,703 for a recovery room, and $16,632 for the scan itself plus doctor fees. The insurance picked up only $1,547.23, leaving the family responsible for the difference: $23,795.47.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9350031/elodie.png)

“I honestly thought it was a mistake,” Elodie’s mother, Annie Nilsson, says of receiving the bill. “There is no possible way anyone could be charged that much for one scan that took 30 minutes.”

Nilsson’s instinct — that these scans should cost a couple thousand dollars — was right. The cost of the same image at other California hospitals is significantly lower. And there was a huge gulf between what the insurance company thought was a “fair price” and what the hospital thought was a “fair price.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3852932/05packard_1024.0.png)

“Elodie has had CT scans, colonoscopies, lots of ultrasounds, so we had assumed the price would be roughly the same,” Nilsson says. “We broadly researched what an MRI should cost, and we thought it would be a couple of thousand dollars. Nowhere in our long back-and-forth with the hospital was there any hint from the people scheduling it that we could possibly see a price like this.”

In a statement, Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital defended the charges.

“Even services that seem routine, like MRIs, can vary dramatically in cost when those services are being provided to sick children,” the statement read. “To make sure we provide the best possible experience and care to our patients, Stanford Children’s employs highly-trained specialists in pediatric imaging.”

It continued: “While we cannot speak to what technology other California children’s hospitals employ or their costs, we know that costs can also vary regionally based on local market demands for labor, supplies, real estate and other essential components of health care delivery. All of these factors impact our pricing, and underlie the amounts we charge for the care we provide.”

Nilsson negotiated the bill down to $16,000, which she now pays in monthly $700 installments. This has made the family budget tight; they already pay $800 each month for a special food formula that Elodie eats, which the insurance plan doesn’t cover at all.

“Every month, I hope they’ll maybe take pity and not send the bill, but of course they do,” Nilsson says. “Sometimes I’m late paying. My biggest issue is, how could the insurance say a fair price is $1,000 and the hospital say $25,000? How could there possibly be such a gap between those?”

Contents

Health care prices in America are high — and they are secret

Elodie’s story is common. Americans pay exorbitant prices for all kinds of care. As a health care reporter, I find myself writing about $25,000 MRIs, $629 Band-Aids — even a $39.95fee just to hold one’s own baby after delivery. People send me these types of bills quite regularly via email.

The health care prices in the United States are, in a word, outlandish. On average, an MRI in the United States costs $1,119. That same scan costs $503 in Switzerland and $215 in Australia.

These are uniquely American stories, and they are the key to understanding our dysfunctional health care system. High prices are hurting American families. Most Americans who get insurance at work now have a deductible over $1,000. High prices are why medical debt remains a leading cause of bankruptcy in the United States, and nowhere else.

As Elodie’s case shows, health care prices in the United States are both high and unpredictable. We rarely know what our bill will be when we enter a doctor’s office, or even when we leave. The prices aren’t listed on the wall or a website as they would be in most other places where consumers spend money.

Today, I am launching a project inspired by these reader emails. My colleagues and I at Vox are asking readers to submit hospital bills through our secure system so we can start getting a nationwide picture of one particular hospital fee, called an emergency facility fee. The reason we’ve selected this fee is because nearly all hospitals charge one for seeking emergency room care, but the price varies enormously and is typically kept secret.

We plan to report back on our findings both here at Vox and in my new podcast, The Impact, a reported series that explores the big challenges in American health care through the lives of people who experience it. If you’d like to participate, there are more details for you here.

As that project launches, I wanted to spell out why these prices are such a problem for the American health care system. Obamacare didn’t tackle America’s high health care prices; neither did the Republican plans to repeal the Affordable Care Act.

Our health care prices explain why reform efforts continue to vex each political party. When you’re paying the highest prices in the world for basic services, for scans and drugs, it will undoubtedly be a struggle to provide all citizens with health care.

This is true for a Republican plan to replace the Affordable Care Act — and a plan backed by 17 Democrats to create a single-payer health care system. The problem is the prices — but right now, there is little political will to fix it.

“It’s the prices, stupid”

In 2003, a team of influential economists published a paper pointing out that prices are the key problem in American health care. It came with the title: “It’s the Prices, Stupid.”

The takeaway was absolutely clear. “Higher health spending but lower use of health services adds up to much higher prices in the United States than in any other OECD country,” the paper concluded.

Johns Hopkins’s Gerard Anderson was the lead author of that report. I called him a few weeks ago to ask if he thought the conclusions of his 14-year-old report still stood.

“The Affordable Care Act reduced the price to consumers, but it didn’t reduce the actual, unit price,” says Anderson. “It essentially made everything affordable to people, but the prices actually accelerated in growth post-ACA.”

But this is not always the story told about American health care. Instead, it often goes like this: We are going to the doctor way too much, and that makes our system expensive. Rampant overuse, unnecessary care, and waste are at the heart of our spending problem.

One poll of 627 doctors, published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, found that 42 percent of physicians thought their own patients were receiving too much medical care. “You’re getting too much health care,” a headline in the Atlantic bluntly declared.

In this narrative, American health care is outlandishly expensive because we take advantage of every new scan, drug, or treatment.

Intuitively, this theory makes a lot of sense to me or to anyone who has become a regular consumer of health care. I’ve had a doctor order an MRI to look at an ongoing issue in my foot, only to forget about the scan completely until I reminded him it existed and asked him to review the results.

But when you start to dive into the actual data, there is scant evidence to back up this theory. If anything, it actually turns out that we go to the doctor relatively infrequently.

Data from the nonprofit Commonwealth Fund shows that on average, Americans go to the doctor four times each year.

Dutch people go to the doctor, on average, eight times each year. Germans make 9.9 annual doctor trips. Japanese residents clock in an impressive 12.8 doctor visits each year — more than three times the frequency of their American counterparts.

“This is really counterintuitive,” says Robin Osborn, who directs the Commonwealth Fund’s international health policy program. “With all the specialists and everything, you’d think we use twice as much health care as everyone. But it’s actually just not the case.”

When Americans do go to the doctor, we tend to have less face time or interaction with our providers. The average hospital stay, for example, is 5.4 days in the United States. This puts us roughly in line with New Zealand and Norway (5.2- and 5.8-day averages, respectively) and with much shorter stays than Canadians (7.5 days) or Germans (7.8 days).

The real culprit in the United States is not that we go to the doctor too much. The culprit is that whenever we do go to the doctor, we pay an extraordinary amount.

“It just feels really crazy”

One way you see hospitals flexing this muscle quite clearly is when you look at a common charge: an emergency room facility fee. I recently produced an episode of my new podcast, The Impact, devoted to this specific health care fee — and you can listen to it here.

This is the price that most hospitals charge for using any sort of service in the emergency room, a base fee for seeing a provider. Hospitals argue that these fees are the cost of keeping their lights on and doors open 24 hours each day, seven days a week.

“We have to prepare for the sickest of the sick,” says Ryan Stanton, an emergency room doctor in Lexington, Kentucky, and a spokesperson for the American College of Emergency Physicians. “So if you come in with a stubbed toe, I still have to be prepared and staffed for the acute heart attack or the gunshot wound, or whatever is coming in.”

Some level of fee to cover these operating costs seems reasonable. But one thing I’ve learned looking at emergency room facility fees is they seem to be set with little rhyme or reason, reflecting American hospitals’ ability to essentially pick their prices.

Take, for the example, a bill I was sent last year: a $629 fee charged for an emergency room visit where a Band-Aid was placed on a 1-year-old’s finger. The bill included a $7 fee for the Band-Aid — and a $622 facility fee.

“I see both sides,” says Renee Hsia, a professor at University of California San Francisco who studies emergency billing and helped me analyze that bill. “I think there are going to be facility charges regardless of the actual service that will always be part of ER care. But where this father has a reasonable point is that when you look at the cost of the Band-Aid and the proportional overhead, it just feels really crazy.”

A few weeks ago, I asked listeners of my roundtable podcast, The Weeds, to send me facility charges they’ve received. The bills range from a low of $533 to a high of $3,170, the facility fee Erika Siegel was charged after a visit to the emergency room at San Francisco General Hospital.

She estimates she spent less than a half hour there, after she flew over her handlebars in a bad bike accident. Her wedding ring had smashed her finger, leaving it badly bruised.

“I mean, what on earth could possibly have cost them $3,170?” Siegel says. “I was so shocked.”

She tried to call up the billing department to get an explanation.

“The guy on the phone said, ‘Well, you know, that information is designated by people who have degrees in medical billing,’” she recounted. “He asked, ‘Do you have a degree in medical billing?’ I was like, ‘Well, you got me there, I sure don’t.’”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9456941/bill_.png)

Siegel wasn’t thinking about a facility fee when she went to the emergency room. She had a smashed finger that looked bruised, and a police officer directed her to go to the emergency room.

Two things stand out in Siegel’s story and in many others — the first being that the bills are incredibly high. The cheapest option I’ve seen so far, $533, would still put a strain on many family budgets.

Second, they are all over the place. Emergency rooms don’t make these fees public, so it’s difficult to predict what you might have to pay.

This is why we’re launching our project at Vox to track these fees nationwide. To understand what’s going wrong in the American health care system, we first need to know what’s happening.

What about Obamacare?

The Affordable Care Act did many things. It extended coverage to millions of Americans and created a more equitable health insurance market that treated healthy and sick patients equally.

But that law did not tackle the unit price of health care in the United States.

“The ACA didn’t change the trajectory at all,” Hopkins’ Anderson put it bluntly.

The ACA made health care more affordable in the sense that more Americans have someone else (Medicaid or a private insurance company) paying the majority of those medical bills.

But the medical bills themselves didn’t actually shrink — and that will vex any effort at reducing the cost of American health care going forward.

Building a single-payer system in the United States, for example, would be a massively more expensive endeavor than anywhere else in the world because of our high prices. When you pay exceptionally high prices for each health service, it quite obviously becomes a lot harder to provide those services to all citizens.

Anderson argues there is little constituency for lower prices in the United States.

“We all say we want lower prices, but we’re not willing to give up anything to get them,” he says. “If you are a major corporation, let’s say General Electric, you want price controls except for the MRI machines you build. If you’re a labor union, you want to control health care prices, except for the salaries of your health care workers. And if you’re a patient, you want lower prices except when you’re sick — in which case, you want everything possible done for you.”

Health care prices are unlikely to fall without some level of government intervention. They may be nudged a little with transparency; Elodie’s family says they almost certainly would have had their daughter’s scan elsewhere if they knew it would cost as much as it did at Packard.

But the cheapest price I could find at a children’s hospital for her scans was still $7,758 — and that’s before additional charges for anesthesia, recovery, and lab work. But only 37 percentof Americans say they have enough savings to cover a surprise $500 to $1,000 medical bill.

President Trump initially showed some interest in regulating health care prices, particularly in allowing Medicare to negotiate drug prices, but so far he has not followed through.

Republicans ultimately put together bills that would reduce government spending on health care but not reduce prices. Instead, it would just shift a greater share of those prices onto patients (the opposite of the Affordable Care Act, which shifted the burden for high prices more to the government).

Our health care legislation in the United States focuses on the question of who pays for health care. In order to have real progress, however, we’re going to tackle a new question: How much do we pay? Until we do, we’re likely to continue living in a world of $25,000 MRIs and $629 Band-Aids that families struggle to pay for.

Source:-Vox