BEHIND the posh Model Town block in Jalandhar, stands the crowded neighbourhood of Abadpura, where a huge section of the Ravidassia community lives. Here, in the serpentine lanes, nestles a small 150 sq-yard house, home to a young voice of freedom and equality.

At a time when the flogging of Dalit youths in Una has triggered protests, Ginni Mahi, 17 years old, is raising her voice and asserting her identity in songs that are finding resonance across the country.

Mahi hails from the community of Jatavs in Punjab and wears it as a badge of honour. One of her lines goes like this: “Kurbani deno darrde nahin, rehnde hai tayyar, haige asle to wadd Danger Chamar (the one who is not scared to sacrifice, the one who is the real thing is Chamar).”

The new voice of ‘Dalit pop’ in the country, Ginni Mahi aka Gurkanwal Bharti, is a YouTube sensation with close to 1 lakh followers. Ready with a new Sufi track on Bulleh Shah and busy with another on Guru Nanak Dev, which she hopes to release in a couple of months, her songs mainly celebrate the lives of Sant Ravidass — founder of the sect to which she belongs — and Dr Bhim Rao Ambedkar, and talk about her community.

She is also expanding her repertoire, bringing up issues such as female foeticide and drugs that ail Punjab. Though she has been singing for over a decade, it’s her two albums in the past year, Guruan Di Diwani and Gurpurab Hai Kanshi Wale Da, and her singles, including Fan Baba Saheb Ki and Danger Chamar, that have catapulted her to success.

In Fan Baba Saheb Ki, she refers to herself as Main thi Babasaheb di, jine likheya si samvidhaan (I am the daughter of Baba Saheb, who wrote the Constitution), while in Danger Chamar she tries to bridge the caste system, stating that members of her community are dangerous only if injustice is meted out to them.

“Baba Saheb spoke for equality and human rights not because he was a Dalit, but because he was an Indian, a Hindustani. He talked about India, gave us rights, empowered us and I salute his fighting spirit,” says Mahi, who puts ‘Bharti’ as her last name to show her “Indian identity”.

While she is certainly not the first to sing about Dalits in Punjab — there have been others such as Chamkila, Roop Lal Dhir, J H Tajpuri, Raj Dadral, Rani Armaan — she is perhaps the first to find such a large audience, an audience for whom she deconstructs her identity. “What is a Chamar. Ch stands for cham (chamda, skin), ma is maas (flesh), and r is rakht (blood). We are all made of skin, flesh, blood,” she said recently.

Her father Rakesh Chandra Mahi, on the other hand, is more guarded. “We avoid her singing on political stages like other singers of her community and even select the lyrics very carefully. Honestly, while we do get disturbed over attacks on the Dalit community, one likes to stay as far as possible from political controversies,” he says. She nods in agreement.

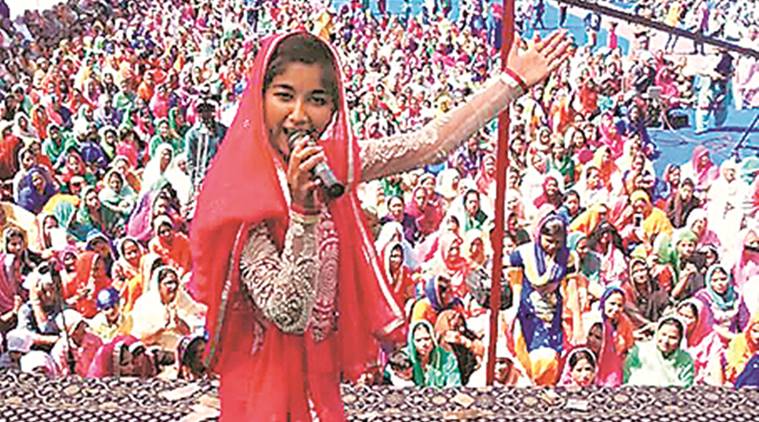

With her powerful, ringing voice and aggressive stance, Mahi is a crowd-puller offline, too, drawing thousands at jagrans, deras and concerts all over Punjab and Haryana. Writing songs along with a team of writers, she has turned the spotlight on her community. “A lot of problems and issues are created around the word ‘Chamar’. I thought about it a lot and shared my ideas with five-six writers, who then wrote about it,” says Mahi.

Women empowerment is another subject she addresses in her songs. One of her singles, “Ki hoya je main dhee han”, highlights female foeticide. “I don’t like the current crop of Punjabi singers who degrade girls in their songs. I feel girls should come forward and oppose it, and assert their rights and change with the times,” she says.

At the same time, she is troubled by the casteism and discrimination being enforced through Punjabi pop culture and films. “For instance, the Jat identity, promoting only one segment of society, is wrong but unfortunately the audience buys it,” says Mahi.

From devotional songs to singing about caste and identity, it has been a long journey. Mahi was just eight when her family took note of her singing talent and her father, who runs a ticketing business, enrolled her in Kala Jagat Narayan School in Jalandhar. She began pursuing music seriously, singing regularly in praise of Guru Ravidass. Eventually, Amarjeet Singh of Amar Audio came on board and produced both Mahi’s albums, “Guran di Deewani” and “Gurpurab hai Kanshi Wale Da”. “People always appreciate devotional music and it sells. Also, don’t all of us like to start our work by remembering God?” asks Mahi.

In her music videos, she may be the muscle-flexing girl but at home Mahi, now a student of music at Jalandhar’s HMV College, is a regular teenager who loves to listen to Justin Bieber and Michael Jackson, worships Lata Mangeshkar, looks up to Rahat Fateh Ali Khan, Shreya Ghoshal and Sonu Nigam, likes painting, and dreams of becoming a playback singer in Bollywood.

As Mahi’s songs of assertion spread across the country, she takes a moment to ponder over art, caste and identity. “You know, a kalakaar (artiste) has no jaat (caste). All this jaat-paat is made by man.”

[source;indianexpress]