As we turned off the main road, there was a mandatory burst of welcoming firecrackers. We had stopped on a slope on slightly higher ground and had walked down the approach, a few hundred yards or so to the open space in front of the main temple at Sriperumbudur, where a red carpet had been laid out.

Stepping out from the front seat, Rajiv Gandhi had said, ‘Come, come, follow me’ and I had demurred, walking to the back and around and then to the front of the car so I could have a bird’s-eye view of the venue, without having to deal with the throng.

‘I have one more question,’ I had said. ‘I’ll wait for you here.’

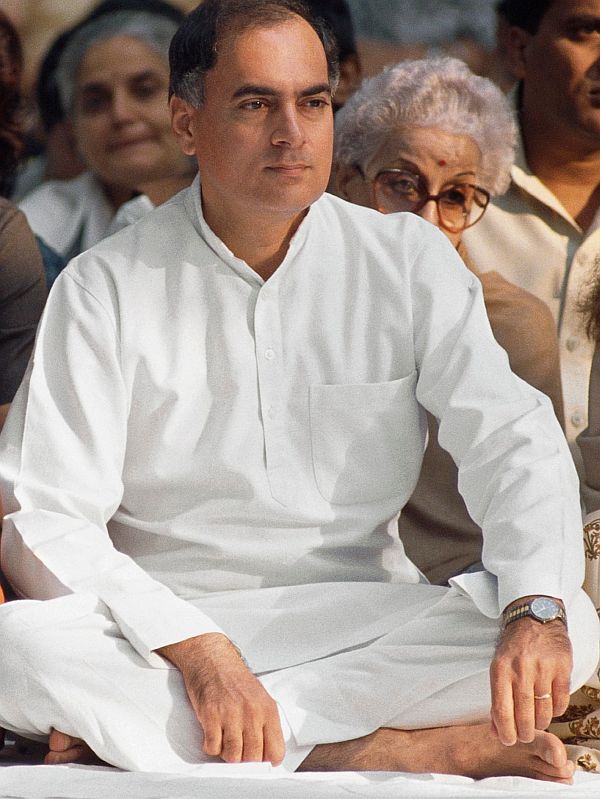

A bomb, a suicide bomber, let alone the first female suicide bomber on Indian soil, was the last thing on anyone’s mind as Rajiv Gandhi plunged into the crowd of supporters on his way to the podium at the far side of the ground, shaking hands, smiling warmly, as was his wont, at everyone who reached out to him.

But as the huge explosion went off a few minutes later and I, standing about ten steps away, felt what I later realised was blood and gore from the victims splatter all over my arms and my white sari, a nameless dread took hold — something terrible had happened to the man I had just been talking with.

Minutes after he walked unhesitatingly into the crowd, there was a deafening sound as the bomb spluttered to life and exploded in a blinding flash.

A moment that, in my head, will always be frozen in time. It was exactly 10.21 pm.

Gone was the excited crowd that had been shouting and cheering only seconds before. In its place were the wails, the screams, as I ran forward; and then, someone behind me pulled me back just in time and said in Tamil, ‘Watch out, you’re about to step on somebody’s arm.’

The revulsion, the horror was complete.

As I fought my way through to the blast site that was only a few feet away, stepping over the debris of the dead and the broken barricades, the one thought running through my head was the fate of Rajiv Gandhi.

He was in there somewhere in that mass of bodies. How serious was it? Could he have survived it? Could he be dead?

And then I saw his body. It was a sight I would never forget.

‘Why is he just lying there? Why doesn’t someone help him up? Someone should get him to a hospital, get him immediate emergency treatment… Where is the emergency medical team? Has someone called the hospital?’ I said out loud. No one was listening.

As the terrified crowd fled from the spot where the dead and injured lay, and bewildered, anxious survivors ran through the gathering throng in the semi-darkness, I spotted Congress leaders G K Moopanar and Jayanti Natarajan, and Margatham Chandrasekhar who had been in the car with me, and at whose behest the former prime minister had made a special effort to address this oddly timed, late-night election rally.

They looked shaken, aghast, devastated at the sight of Rajiv Gandhi’s prone, seemingly lifeless body. Margatham looked shattered, as if her world had ended. Rajiv Gandhi had only come to Sriperumbudur at Aunty’s request.

The next day both Natarajan and Moopanar would separately tell me how they had tried to lift Rajiv Gandhi from the ground but couldn’t as his body ‘simply disintegrated in their hands.’

Worse, how at that crucial moment, they couldn’t find a single policeman, barring Rajiv Gandhi’s personal bodyguard Pradip Kumar Gupta who was lying right next to Rajiv Gandhi and had died in the blast.

There was no ambulance — now an accepted fixture at election rallies. They couldn’t find any medical personnel, or a stretcher or gurney or even a vehicle to get him to the nearest hospital.

In fact, within minutes of the blast, two cars, one a white Ambassador flashing a red beacon, and another that came from somewhere in the back, had backed on to the main road and sped away.

The mood on the ground was getting decidedly ugly. At the spot where Rajiv Gandhi’s body lay, it was getting more and more difficult to hold one’s ground as his supporters closed in, muttering unintelligibly under their breath.

From the corner of my eye, I finally saw a vehicle that I presumed was an ambulance, lights flashing, trying to make its way from the main road that we had left only minutes earlier.

Blocked by the crowd, it was inching its way forward. I had to move with it, follow the ambulance carrying Rajiv Gandhi’s body, take the story to its logical conclusion.

By a stroke of luck, as I was pushing my way through the crowd, trying to find the car that I had hired for the evening, Rajiv Gandhi’s driver emerged from the melee. I didn’t know him personally but he called out to me and said he had been looking for me everywhere.

Catching me by the arm, he said, ‘We should leave; it’s not safe here. Anything can happen. Let’s go, let’s go, I will take you back to Madras. Once the protests start, there will be riots, they will block all the roads; we won’t be able to get back.’

Brushing aside my protests about abandoning the Congress leaders if we left, and how we should stay with Rajiv Gandhi’s body, he insisted that I go with him, assuring me we would follow the body, which we were anyway ill-equipped to transport.

With no sign of my driver and realising this was my only way back to the city, I jumped in as he quickly reversed the car. We inched our way out of the venue as I continued to scan the scene for my driver who was nowhere to be found.

We followed the ambulance to a hospital just ahead; checked whether Rajiv Gandhi’s body would be kept there overnight and, receiving conflicting, contradictory reports from the bewildered medical personnel there, with no one ready to confirm or deny that he had indeed died, we raced to Madras before the mobs had a chance to block the roads into the city.

At the Central Telegraph Office on Mount Road, as I typed the copy, for once the sleepy telex operators were all awake. They stood behind me, their jaws dropping, reading the story as I wrote it.

Rajiv Gandhi was dead. Assassinated at 10.21 pm on 21 May 1991.

Once I filed the story I returned to my uncle-in-law’s apartment on Harrington Road in Madras, where was staying.

My husband’s wonderful uncle, M K Ramdas, was fielding all calls, including the critical one from his cousin M K Narayanan (who was also my husband’s uncle). Narayanan headed the Intelligence Bureau and wanted every single detail of the night’s terrible events.

He listened patiently as I described what I had seen, asking me repeatedly about the ring of fire that I insisted I had seen around Rajiv Gandhi as he lay on the ground, minutes after the bomb had exploded.

Only much later would it hit me that if there was indeed a ring of flames around the blast site, it would imply the use of landmines.

The next morning, an IE team assigned by Narayanan came to hear my account after they had reconnoitred the Sriperumbudur area. They said they saw no evidence of a ring of fire, but conceded that what I had seen must have been the flames when the victims’ possessions and clothes caught fire.

They listened as I described the shocking lack of security for a former prime minister who had only four years earlier survived an assassination attempt in Colombo by a Sri Lankan naval rating.

Even at that point, as we mourned the death of a wonderfully warm human being, few had a clue about who was actually responsible for the killing. The investigators hadn’t yet gone public with the fact that a senior policeman and his team had stumbled upon a camera that had captured telling images of Rajiv Gandhi’s assassins.

I was in limbo, in some sort of a bubble. In shock. It was only when I got back to my parents’ home in Bangalore and my normally undemonstrative parents enveloped me in a highly unusual bear hug that I began to shiver uncontrollably and allowed myself to cry and mourn the passing of Rajiv Gandhi.

The full horror of what I had witnessed, and the images and emotions that I had blocked and suppressed for seventy-two hours came rushing back.

On 24 May, the nation stayed riveted to television screens as the funeral, attended by dignitaries from over sixty countries, was telecast live.

The mortal remains of Rajiv Gandhi were consigned to flames on the banks of the Yamuna; his stoic son, Rahul, and daughter, Priyanka, the cynosure of all eyes.

Days later, I received a call from the Indian embassy in Abu Dhabi. Rajiv Gandhi’s widow had sent a message asking me to meet her at their New Delhi home at 10, Janpath.

I flew to Delhi on 31 May and, as I walked from the Congress party office to the pathway that led to the house that Rajiv Gandhi had called home, alongside the Gandhi man Friday V George, I was accosted by several senior Congressmen, saying I must find out at any cost, whether Sonia Gandhi would lead the Congress party!

Inside, in a room lined with books and a long table where Rajiv Gandhi had often been photographed confabulating with his Cabinet, was Sonia Gandhi, her face devoid of make-up, a far cry from the beautifully coiffed creature whom I had met on her visit to Dubai a few months ago.

She reached across, held both my hands in hers and said, ‘Tell me everything, tell me what he said, what mood was he in, what were his last moments like. I want to hear it from you, every tiny detail. Was he happy, was he tense, what were his last words…’

Tears streaming down her cheeks — and, I realised, mine too — and still holding on to my hands, she listened as I recounted the last forty-five minutes of India’s youngest prime minister’s life; his unexpected death closing the chapter on India’s all too brief Camelot.

Tears streaming down her cheeks — and, I realised, mine too — and still holding on to my hands, she listened as I recounted the last forty-five minutes of India’s youngest prime minister’s life; his unexpected death closing the chapter on India’s all too brief Camelot.

[source;rediff.com]