India has grown up before Sylvia Dyer’s eyes. She was 19 when Independence came and remembers a letter arriving from the British High Commission in Calcutta asking her Anglo-Indian mother to move to the United Kingdom because they could no longer be responsible for their safety.

“Where do we go? This is our country, our home, the only home we’ve ever known. This is where I’ll live and die,” said her mother Gladys, wrote Sylvia in a fascinating account of life in pre-Independent India in The Spell of the Flying Foxes (Penguin Books India 2011).

Gladys died in India and was buried in Dhang, Bihar, where she lived; her three sons moved to England after her passing but Sylvia, her only daughter, stayed on. As a five-year-old, Sylvia had survived the earthquake of 1934 that devastated the untamed and beautiful land of Champaran. Her grandmother and aunt were killed in that great Bihar quake that old-timers still remember for its ferocity.

In a life which is a commemoration of gritty survival, Sylvia Dyer has fought the good fight. After a memorable childhood, she married twice, both times to men in the Indian Army, and widowed twice, rode out the ’65 war as an army officer’s wife in Kashmir, courageously faced the death of a young son and now lives alone with her memories and a treasure trove of history as seen through her eyes.

“The earthquake was the most terrible thing of my life. I was terrified and we spent the night waiting for the two mothers who had died. We lived with the cows after our house collapsed. It happened so many years ago but even now I don’t like to talk about it,” says Sylvia Dyer, 87, on a quiet evening in her home in Pune.

The well-kept house has sepia-tinted pictures of family in classic frames. A brass memento presented by the army to her husband, Brigadier Aloysius Dyer, who had fought in the Second World War like India’s famous field marshals – Cariappa, Thimayya and Manekshaw – is placed with the photographs.

There’s a garden outside that she loves to spend time in. Sitting under a soft yellow light, Mrs Dyer is dressed elegantly; the advancing years have fogged her memory in patches. But her frailness hasn’t diminished her delicate beauty.

Our collective history as a people survives when people who have lived it, survive to tell the tale. It is through the people’s individual histories that we learn about what the past must have been, and the changes that have taken place that have brought us to the present. Sylvia Dyer is one such. The excavations from her memory weave a tapestry of life lived in a far distant time, some vaguely familiar, some completely forgotten.

Dhang, on the banks of the Baghmati river in the wilds of Champaran, Bihar, was where she spent her childhood on a plantation started by her great grandfather in 1848. Alfred Augustus Tripe had sailed from England to India in search of Indigo, the ‘Blue Gold’ which at that time was the only blue dye in the world and thrived in the soil of Champaran, writes Sylvia in her book.

When German factories started making synthetic dyes and political changes brought about by Gandhiji’s movement crippled the Indigo business, the family’s fortunes suffered. But what they had in plenty was land.

They grew paddy, sugarcane, bamboo, fruit, went hunting, reared chicken, cows and pigs. A cousin even tried rearing elephants but the venture failed.

Tripe had married an Indian Rajput lady and prospered. He made an English double-storeyed house on land received as dowry which was destroyed in the earthquake. When his grand-daughter and only heir – Gladys – built a new home she ensured it had a single storey so that no more lives would be lost under its walls.

“My grandmother Gladys inherited this vast property and ran it. She was the matriarch of the family, who was widowed twice,” says Marilyn Dyer, 48. “We have a history of strong women in the family. Once there were two women alone in the house when they were attacked by dacoits and they fought them out. My grandmother could shoot from horseback.”

Champaran still has remnants of crumbling Indigo godowns set up by the British. Seventy years after Tripe arrived and long after his death, Gandhiji launched his first satyagrah against the British by protesting the exploitation of Indigo farmers. His initiation into the freedom movement began in these lands. The wheels of fate turned such that 100 years after Tripe’s arrival, when time came to choose between India and England, his great-grand daughter Gladys and her only child Sylvia chose India.

This was home.

“My mother’s three brothers took residence in the UK, the youngest stayed with the Indian Army,” says Gladys’s grand-daughter and Sylvia’s daughter Marilyn. “Mum is very Indian and would not have liked it there. She was also an army wife.”

Sylvia’s father worked with a tea factory in Calcutta but moved to Dhang to help look after the land. A faraway place, one that her daughter Marilyn says “did not even show up on the map till recently”, Dhang belonged to another time.

‘Nobody would ever forget Dhang, though after all these years it seems to me that it never really existed, and was just a long ago, stretched out dream,’ writes Sylvia in her autobiographical book.

At the edges of the land spread out the thick jungles and beyond them rose the Himalayas, just 25 miles away. There were rows of sheesham trees with stories of bats resting on their branches, the nearest doctor was 50 miles away, the tiny railway station saw only one train that came bringing in newspapers, letters and bread, there was a wrestling akhara, a notoriousdaaku came as a saviour after the earthquake and remained a lifelong friend.

“Oh dear, I have become very old,” says Sylvia Dyer, “but we did such silly things as children. We had 10 dogs and I had a big orange cat. We had a big place with ages and ages of distance. Big fat rats used to fly out of the fields during harvesting,” she laughs.

Shortly after India was free, Sylvia married an Anglo-Indian army officer, Ronald Pereira, from the Gorkha Regiment after meeting him in the Muzaffarpur club. When the Banihal tunnel that would link Jammu and Srinagar was being constructed, Sylvia’s husband was posted in Banihal.

“They were stationed in the middle of nowhere. Their house used to be a sheep stable. When he was posted in the forward areas she would go to Dhang with her two boys,” says Marilyn in a Skype conversation from Hong Kong.

Officer Pereira tragically died of high fever, while travelling alone on a train journey back to his post from a holiday. He left behind a widow with two young boys.

“Some very bad things happened after my husband died. My two little boys had to be sent to a boarding school and I went back home to look after the small of plot of land in Dhang that my mother had left me. A lot had changed by then and I stayed on the fields till the sun went down everyday. It was hard,” says Sylvia Dyer, reminiscing about those days.

It was the early ’60s, zamindari had been abolished and only a fraction of the land remained. She hired people and worked the land but the crop failed because of a poor monsoon.

“She was devastated,” says Marilyn, “But mum is a survivor and extremely spiritual, not in the Bible thumping way. She just puts her troubles up to the universe and things happen.”

Just as things were crumbling around her in her beloved Dhang, two of her friends from the army invited her to spend some time with them in Srinagar. When she packed her bag to leave, Sylvia did not know that life was to take yet another decisive turn.

In Sringar, she would meet Brigadier Aloysius Dyer, a 50-year-old bachelor who had served in Mesopotamia, Egypt, Burma and India.

Born in 1914, Aloysius Dyer was working in the Reserve Bank in Bombay when World War II broke out. He decided to sign up for the war and joined the Army Service Corps that was the only branch taking in recruits. “But he hardly served the ASC and was posted all over. He was decorated with an MBE in Burma and knew Field Marshal Sam Manekshaw very well. He was also General Thimayya’s staff officer,” adds Marilyn.

The sub area commander of Jammu and Kashmir, Brigadier Dyer and Sylvia were married within a year of meeting. After a quick and magical honeymoon in the most beautiful place on earth, the army officer spent most of his time in a bunker planning his troop movement when India went to war with Pakistan in 1965 while his bride stayed in the house.

Brigadier Dyer retired soon after the war and moved to his hometown, Bombay. They finally settled down in Pune where he died of cancer in 1988.

“Her own father died when she was three, she lost both her husbands, one of her boys died in a road accident on Dadar bridge. She had a tough traumatic life but however bad things were, mum always had a sense of humour,” says Marilyn, adding that her mother learnt to drive in her late 30s, was an accomplished soprano, learnt to use the computer at 70, published her memoirs at 83 and used to do the drilling and wiring of the house herself.

Sylvia Dyer’s life captures an India of a different time, one that no longer exists or is fading away like her own memory. Her stories and anecdotes are what family stories and histories are made of. The ones that go down generations – and hers are populated with Anglo Indians, memorable characters, and memories of a childhood in a forgotten land where her ancestors lie in quiet graves. But she doesn’t know if the graveyard remains or has been desecrated or run over by weeds or has sunk into the earth.

In 1970 she sold whatever was left of the land in Dhang to local Rajputs and hasn’t been back since.

“It is all very personal to her. It would be like going and looking at a corpse. She’s never let me go there but I’m determined to go,” says Marilyn.

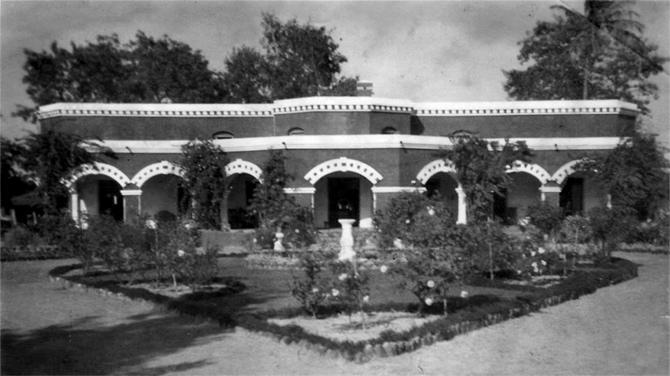

Sylvia Dyer’s book cover has a picture of the home she grew up in. It is painted red and white, with arched verandahs surrounded with trees.

The concluding pages of the The Spell of the Flying Foxes book captures her journey back from boarding school, as she hops off the train at Dhang’s tiny railway station and makes her way in a bullock cart to their home. The mud track goes past fields, groves and sheesham trees.

‘And there before us, set in the kaleidoscope of colours is — Home!’ writes Sylvia Dyer. Her vivid descriptions almost takes you there.

[source;rediff.com]