/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/56295453/GettyImages_664519206.0.jpg)

This is the web version of VoxCare, a daily newsletter from Vox on the latest twists and turns in America’s health care debate. Like what you’re reading? Sign up to get VoxCare in your inbox here.

You hear a lot about how much Medicaid pays health care providers and whether the program provides its patients adequate access to doctors and hospitals. One Democratic senator is looking to effectively end that discussion.

Right now, the facts on the ground are complicated: Medicaid actually pays hospitals about the same as Medicare does on average, though it does generally pay doctors less than its sister program. Medicaid patients don’t report that their medical needs are going unmet any more than do people with Medicare or other kinds of insurance, but they are more likely to say they have had trouble getting a doctor’s appointment.

So some real disparities exist, even if they may be exaggerated in the political rhetoric. But a new proposal by Sen. Brian Schatz (D-HI) seeks to eradicate them altogether.

Tucked inside his Medicaid-for-more plan is a provision that would align Medicaid reimbursements with those of Medicare. I confirmed with Schatz’s office that this would apply to the whole Medicaid program, at least as the plan is currently conceived.

“Frankly, it would dwarf the other parts of this bill,” Chris Sloan, a senior manager at Avalere Health, an independent consulting firm, told me.

This is where I point out that Schatz’s proposal almost assuredly won’t become law. But in terms of signaling where Democratic health policy is heading, it is still significant.

Other experts in the area agreed with that assessment.

“It would be a major change in the program to go in this direction,” said Stephen Zuckerman at the Urban Institute, who has written extensively on Medicaid reimbursement policy.

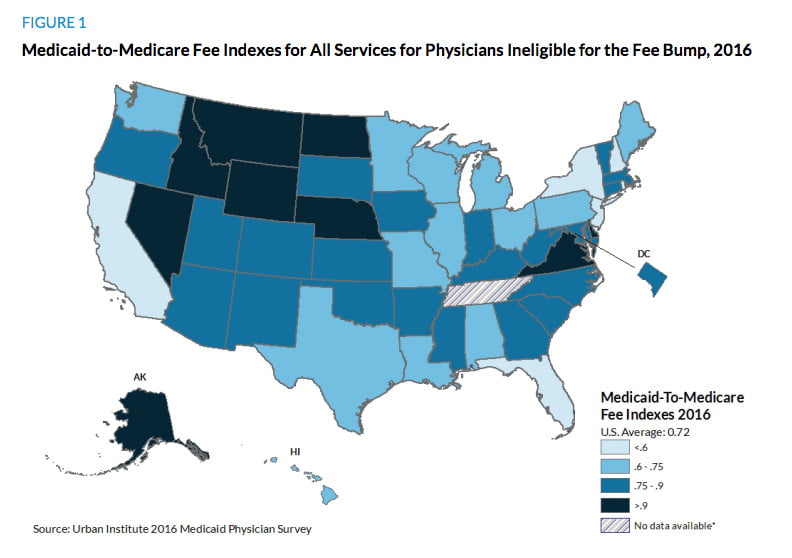

There is a real gap to be made up, especially with doctors. Spending varies widely across states, but on average, Medicaid pays physicians 72 percent of what Medicare does, Zuckerman’s research has found.

While lower reimbursements aren’t the only reason doctors might turn away Medicaid patients, it is certainly a factor. About two-thirds of doctors acceptMedicaid — lower than Medicare or private coverage, but not as dramatic a difference as some of the program’s critics suggest.

Still, increasing Medicaid reimbursements, as Schatz is proposing, would likely further close any access gaps that currently exist.

We actually have some recent evidence of this. Obamacare included a temporary two-year bump in Medicaid payments for certain services in the lead-up to the law’s Medicaid expansion in 2014.

Zuckerman and a group of researchers found that the availability of appointments for patients increased by 7.7 percent during that period, and the increases were greatest in the places that saw higher reimbursement boosts.

It’s hard to know whether that was because more doctors accepted Medicaid or because doctors who already accepted Medicaid made more spots available to the program’s enrollees, or a combination thereof, Zuckerman told me.

But the point is: Medicaid patients found it easier to get an appointment after the pay increase — and that increase was only temporary.

“If you actually committed to a long-term change in Medicaid physician fees, I would suspect that physicians would really consider their relative willingness to participate in Medicaid,” Zuckerman said. “If you had Medicaid fees up at Medicare levels, you would think you would close some of these gaps.”

This would cost money, of course. Schatz is proposing that the federal government pick up the full cost of the increased reimbursements.

The Congressional Budget Office estimated that the temporary increase in Obamacare would cost $8 billion a year, and that was for a more limited set of services than the Schatz plan touches. Schatz hasn’t specified exactly how he would pay for any of the new spending in his proposal.

But as Medicaid flexes its political muscle and Democrats like the senator from Hawaii begin dreaming of bringing more Americans into its fold, the question of reimbursement is going to keep coming up. This gives us one example on how some on the left might try to address it.

Chart of the Day

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9096641/ScreenShot2017_08_22at3.15.03PM.151526.png)

The geographic diversity in Medicaid payments. It can’t be said enough: While the numbers above give you a general sense of what the status quo is and how it could change, any increase in Medicaid policy is going to affect every state differently. This chart, from Zuckerman at the Urban Institute, gives you an idea of how much reimbursements vary across states.

Kliff’s Notes

With research help from Caitlin Davis

Today’s top news

- “Senate panel plans 2 hearings on girding health insurance”: “The Senate health committee will hold two hearings early next month on how the nation’s individual health insurance marketplaces can be stabilized, as party leaders grasp for a fresh path following the collapse of the Republican effort to repeal and replace much of former President Barack Obama’s health care law.” —Alan Fram, Associated Press

- “Fearing sabotage, groups prepare ObamaCare blitz”: “State and local groups that help support ObamaCare are springing into action ahead of an enrollment period they fear could be sabotaged by the Trump administration.” —Rachel Roubein and Jessie Hellmann, the Hill

- “Republicans organize to raise concerns about Medicaid expansion in Maine”:“Several Republican lawmakers are expected to announce their concerns Tuesday about expanding Medicaid, a first step toward what could become a formal campaign to oppose the question voters will face on the Nov. 7 ballot.” —Scott Thistle, Portland Press Herald

Analysis and longer reads

- “A Health-Care Fix That Works, Now Being Rolled Back”: “Last week the Department of Health and Human Services announced plans to scale back bundled payments in joint replacements and cardiac care. This is bad news for patients and doctors alike.” —Jason Furman and Bob Kocher, Wall Street Journal

- “MACRA proposals flood in”: “The AMA, HIMSS, CHIME, the American Medical Informatics Association and Health IT Now all got their comments in under the wire, with the final rule expected sometime this fall. Each group has different beefs and blessings, of course, but here are a few salient points.” —Arthur Allen, Politico

- “Hospitals Could Do More For Survivors Of Opioid Overdoses, Study Suggests”:“Clinicians and researchers trying to get a handle on the epidemic look at those nonfatal experiences as opportunities to jump in and figure out whether there is overprescribing going on or whether the patient needs help getting treatment for an addiction. But a paper published Tuesday in the Journal of the American Medical Association, suggests such interventions don’t happen often enough.”

Source:-NPR